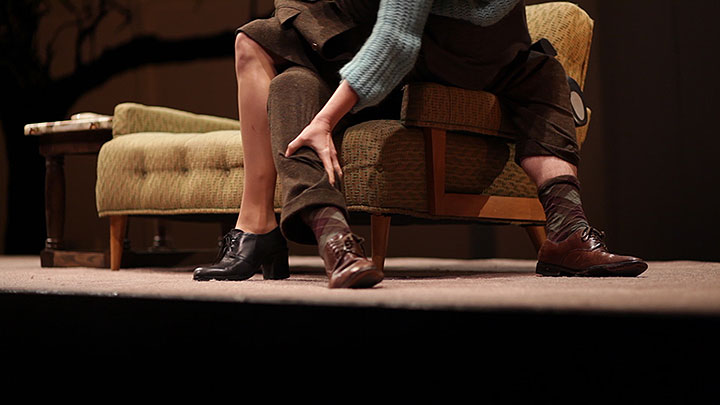

LOVERS

Set Design: Brett Banakis | Lighting Design: Mary Louise Geiger

Costume Design: Kim Krumm Sorenson | Sound Design: Daniel Kluger

Scroll down to read Drew's director's note for Lovers for TACT in New York City.

Lovers (“Winners”/“Losers”) by Brian Friel | Director's Note

Brian Friel, one of the world’s most celebrated living dramatists, is famously cagey about the meaning of his plays and even more famously critical in his assessment of their merits. When asked in a 1970 interview which play had given him the most satisfaction, he replied, “I couldn’t answer that. All I can say is that I think the first part of ‘Lovers’ is probably something I remember with a certain affection.” Considering the source, this is high praise indeed.

In addition to the playwright’s personal endorsement, Lovers earned three Tony nominations (Best Play, Best Actor and Best Featured Actress) when it premiered at the Vivian Beaumont Theater in 1968. Yet since that first production, the two plays that make up this beguiling early work have rarely been paired together again on a New York stage.

In 1964, after spending six months observing Tyrone Guthrie at his recently opened theatre in Minneapolis, Friel—who was then known primarily as a writer of short stories—returned to Ireland with a rekindled sense of energy for playwriting. His next endeavor for the theater, Philadelphia, Here I Come, demonstrated his commitment to experimentation, with a central character split into two separate selves: Public Gar and Private Gar. It proved to be a career-making success. Using two parts to embody the mysteries, complexities, and contradictions contained in a unified whole, Friel, in effect, unveiled what would become a lifelong artistic obsession for him: the capacity of theater to articulate “the burden of the incommunicable.”

A few years later, Friel explored the effect of theatrical dichotomy further by creating a single play, Lovers, out of two separate halves: “Winners” and “Losers.” In this country, especially, the two pieces have too easily been separated over time, often performed as solo one-acts or in combination with short plays by other authors. (True to its title, “Winners” takes the prize for most frequently performed of the two.) Yet the real power, and the fully Frielian sense of “life’s rich, indivisible complexity,” comes from experiencing the plays together as they were originally conceived. Only by considering how these two plays oppose and reflect each other, how intertwined they may be despite their differences, can we appreciate the scope of Friel’s compassionate vision. Only then can we fully grapple with the ways he subverts our innately human desire to find answers where only questions persist.

Much is revealed in these two plays, but so much more remains unsaid about the lives of Catholics in Northern Ireland in the mid-1960s. Though written and first performed during the relatively calm years (1966-1968) before The Troubles erupted with the Derry Uprising in October 1968, Lovers nevertheless offers glimpses of the particular sadness and frustration that plagued Catholic society in Northern Ireland, after a decades-long struggle to gain civil rights and economic equality under the Protestant-controlled government. To be Catholic in the North was to live on the fringes of society, enduring institutionalized discrimination. As a child, Friel recalls:

There were certain areas one didn’t go into. I remember bringing shoes to the shoemaker’s shop at the end of the street. This was a terrifying experience, because if the Protestant boys caught you in this kind of no-man’s-land, they’d kill you. I have vivid memories when I was twelve or so of standing at my own front door and hoping the coast would be clear so I could dive over to the shop; and then, when I’d left the shoes in, waiting to see was the coast clear again. If you were caught you were finished. It was absolutely terrifying. That sort of thing leaves scars for the rest of one’s life.

Growing up within this ‘Us’ versus ‘Them’ framework (“Losers” versus “Winners”) made Friel particularly receptive to nuances of social alienation. In his plays, we experience this in the form of dialogue that is seldom an equal give and take. Moments of conversational equilibrium are rare and delicately negotiated; more frequently, conversation is heavily one-sided—an exchange of monologues indicating a subtle struggle for power. Looking over his oeuvre, Friel acknowledges a pattern:

There are very often two characters: one who is a very extrovert, quick-talking, glib character and another who’s a kind of morose and taciturn and … less immodest, let’s say. And in some way I think perhaps those reflect some aspect of myself and perhaps some aspect of a member of the minority living in the North.

At the same time, Friel recognizes that instability of surroundings can lead to a certain flexibility and receptivity of character, affecting how one imagines oneself fitting into the world. “A continual openness to new possibilities of accommodation is crucial,” he observes.

In Lovers, by employing a wide array of narrative devices, and an approach that is at once thoughtful and playful, Friel asks us to notice how we participate in the storytelling of our own lives. His beguiling use of language tricks us into accepting initial impressions and then leaves us to contend with feelings of loss and confusion when our preconceptions go unconfirmed. With a unique sensitivity and clarity, he exposes a major paradox of human relationships—the necessity of developing our innermost self through our interactions with others. As an audience, our experience of the two halves of Lovers mirrors the experience of Friel’s characters. We participate in their attempts to navigate the world, struggling to maintain a sense of self as we decode the mass of signals—some pertinent, many irrelevant—that make up their gloriously inexact attempts at communication.

Friel recognizes we go to the theater to have our sense of reality challenged, if not changed. “We don’t go to art for meaning,” he observes. “We go to it for perceptions of new adjustments and new arrangements.” From his personal exploration of how form impacts narrative, to his depiction of characters who self-dramatize as a means of coping, Friel takes on life’s struggles and mysteries without reserve. He fully embraces the destabilizing nature of theater, offering moments of joyful humor in the midst of tragedy and moments of excruciating pain amid flat-out farce. We are all actors in a Brian Friel play. The essential passivity of his characters only underscores that fact; to understand their stories, we must piece them together ourselves and thereby take some responsibility for their legacy.

Friel himself remains, characteristically, noncommittal. As his play, The Loves of Cass McGuire, was beginning rehearsals for Broadway in 1966, he gave an interview to the Belfast Telegraph. Reluctant to either express optimism for the new play or assign much significance to the success of Philadelphia, Here I Come, he turned his attention to his next project, which would become Lovers. “I am trying to work on an idyllic love story,” he said. “But I may have thought about it too long. It hasn’t got a title yet. I don’t know if it will ever come to anything.”

-Drew Barr